The Rana Plaza incident happened in April 2013. This incident awoke the world to the poor labour conditions faced by workers in the ready-made garment sector in Bangladesh. Any brand whose label was found in the aftermath, among the debris, faced a lot of flak. As a result of this accident, for example, Disney decided to remove its entire production sourcing out of Bangladesh.

Since the 1970s, Nike has been accused of using sweatshops for their shoe production. These issues came to the fore more recently, in the 1990s, where it got a lot of bad press.

Why did these incidents take place, and why is it that the chances of this happening again continue to be high?

Brands have been on PR overdrive with highly publicized policy changes and code of conducts. Is this just lip-service? What’s really going on?

It comes down to the basic business model of the garment industry – scour the globe to find the place with the cheapest labour cost, to make the product.

If we look at the apparel industry in particular, you can see how this strategy has worked wonders, over the years.

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, prices for apparel were 3.23% lower in 2021 versus 1990. A garment which would have cost $20 in 1990, would actually cost less in 2021.

Let’s put it another way – between 1990 and 2021, apparel experienced an average inflation rate of -0.11% per year.

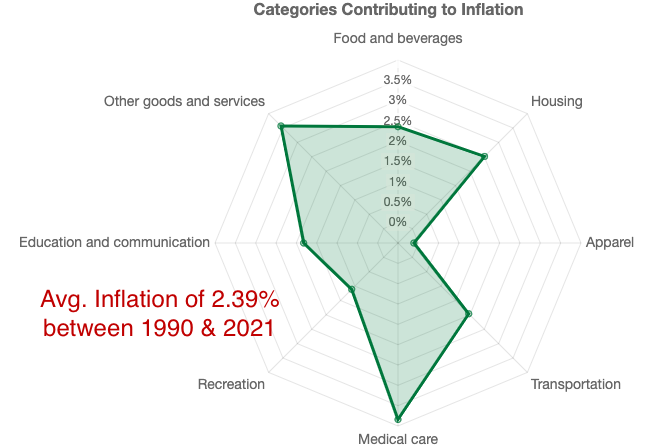

In the meantime, here is what was happening in the some of the main categories of the Cumulative Price Index (CPI), during the same period.

The price of apparel has come down over the last 30 years, while some of the other categories have witnessed a healthy rate of inflation.

A garment costing $20 in 1990, would actually cost less in 2021

US Bureau of labor statistics

The Factory Perspective

Think about it – you’ve been in the business of manufacturing Readymade Garments (RMG) for the last 30 years. During this period, your buyer has constantly pressurized you to maintain pricing or even lower your price. The sword hanging over your head is always that of the unknown factory, in some part of the world, who can do it for cheaper.

So you invest in upgraded machines, to improve your productivity. Most of the times, this is through a bank-loan. You continue to service the pricing needs of the brand, by maintaining or lowering your price.

When you look at your financials, here are your options:

RAW MATERIAL – Fabric: You could alter the quality of the fabric ever-so-slightly, so that you can perhaps save a penny a piece eventually. The risk is that big brands have their own litany of testing requirements and inspectors who are well-versed in the ins-and-outs of all raw material parameters. Do you really want to risk a claim?

RAW MATERIAL – Trims & Accessories: Same issue as fabric

FINANCING CHARGES: Your factory has a working-capital loan or a line-of-credit from your bank, as many big brands work only on credit terms (such as, payment 90 days after shipment of goods). You really do not want to mess with the banks and default on your interest payments

OVERHEADS: This is electricity, rent, maintenance – the normal stuff – add to this fire-fighting equipment, in-house medical facilities for workers. As a factory-owner, you look at this cost head, and realize that maybe you do not need to install all the fire-fighting equipment, or have an expensive annual maintenance contract for servicing your fire-fighting equipment. After all, what are the chances of your factory catching a fire? So you start doing some much-needed cost-cutting here.

WAGES: This is the big variable when it comes to your production cost. You look at the manuals of the various social audit programs; you can look at the minimum wage requirement of your local government; then you plug those numbers into your spreadsheet, and you find that it is actually impossible to even break-even if you pay so much. So what do you do? You make the workers work more hours, in order to average out their daily wages. You do not guarantee fixed employment, and instead work on a “per-piece” basis.

ROLE OF SUBCONTRACTORS: Now if you have more orders than you can handle, instead of adding more workers, you start subcontracting your work to the myriad network of no-name subcontractors, and you pay them even less than you would to the workers in your own factory – all this is helping you save cost, and more importantly climb yourself up to a bare minimum.

GOVERNMENT INCENTIVES: In many developing countries, the government offers some sort of incentive to the exporter, which is a percentage of the value of goods exported. It is not uncommon for exporters to view this as the only margin they can earn – the incentives can start from 1% and upwards.

EXCHANGE RATE: As a factory-owner, exporting RMG products overseas, this factor is probably your best friend, and your way out of the financial mess. If you sold a product for $1.50 say at a time when the exchange rate was INR 70 to 1 USD, you hope that by the time it is ready for your buyer to pay you, that your local currency gets weaker, and you can perhaps extract a little extra money in your local currency, through the deal.

You realize that maybe you do not need to install the fire-fighting equipment…after all, what are the chances of your factory catching a fire.

MANAGING COSTS

So that’s an average business landscape faced by a factory owner, in this space.

The underlying principles governing how they are operate, are based purely on survival:

- With such low or negligible margins, high volume is the only way to get past all the financing and overhead charges

- Reduce overhead charges so that this equation becomes a little better and a bit more manageable

- Squeeze the workers and make them work longer hours, so that your cost of garment comes down, just a tad

Meanwhile, the brands…

Let’s focus back on the brands for a second.

Since last year, brands have been making so much of noise on social media and using their vast PR machinery, to espouse the virtues of finding alternative sustainable material for their products.

And yet, when it comes to looking at the social impact of their business, which goes beyond having a chief diversity officer – the real social impact being how the factories operate – most of them are shy to even list their core factories.

Fashion Revolution, which comes out with the Fashion Transparency Index, in its 2021 report, noted the following:

“Transparency is not to be confused with sustainability. However, without transparency, achieving a sustainable, accountable, and fair fashion industry will be impossible.

Fashion Transparency Index Report, 2021

Transparency underpins transformative change but unfortunately much of the fashion value chain remains opaque, while human and environmental exploitation thrives with impunity.”

Less than 50% of the 250 largest fashion brands and retailers, agreed to disclose their manufacturing facilities.

FASHION TRANSPARENCY INDEX REPORT, 2021

Is there a solution?

Critics can say that paying more is not the elixir to solving the human exploitation prevalent in factories. True, it’s not the single factor. However, how about we start acknowledging this issue as a factor?

The fashion industry ‘s success is based on smokes and mirrors. They do not want to reveal what happens behind the scenes. How about creating more transparency in who is making the product, to start with? An increasing number of cosmetic companies are printing their carbon footprint on their product labels.

One way to start would be to have a QR code on every label, so that the consumer can look up the factory details online.

In hearing conversations about how to “solve” this problem, some observers talk about going beyond spreadsheets to new-age technology solutions involving blockchain. Some talk about the need for having more aggressive factory inspections by the brands.

Perhaps these are part of the solution, but it all starts with intent. The brands have to be willing to charge more or reduce their profits. Without this, we will continue to form non-profit organizations and hold seminars about this topic, while concrete, actionable help for the exploited workers, goes unnoticed.

According to a recent 2021 Fashion Industry Benchmarking Study, a majority of the brands are looking to strengthen their relationships with key vendors. This is a positive development. To strengthen such relationships, there has to be an underlying level of trust, where the factory feels that the brand customer is going to be more invested in their factory’s well-being, and not just make it a transactional relationship.

A more detailed commentary on this report, can be found here.

COVID has created an opportunity for the fashion industry to recognise that it’s at an inflexion point. The “business as usual” comes at a cost, which very few end-consumers are even made aware of. Instead of hiding the vendor factories in the deep shadows, like a dirty-little secret, perhaps the time is ripe to flaunt the factories and make them part of your overall branding efforts.